Rethinking AGI Safety Through Invariants

Introduction

In debates about AGI safety, we often disappear into equations, policy frameworks, and technical constraints. Yet beneath all the math and governance models lies a simple truth: civilization doesn’t collapse all at once. It unravels at the edges — in the ignored signals, in the small fractures, in the people who leave long before anyone else notices danger.

To build safe and trustworthy AI, we have to listen to those signals.

The Problem: Scale, Safety, and Drift

Most current AGI safety frameworks answer a single question: “What are we optimizing?” But they rarely ask the deeper questions: for whom? at what scale? over what time horizon? These distinctions matter immensely — because optimization without context can blindside everyone.

Single-scale optimization narrowly tunes for one domain (e.g., compute efficiency or local user benefits), but overlooks ripple effects at other layers — whether societal, environmental, or intergenerational. It’s like tuning a car engine for speed without checking how it affects emissions or road safety.

Federated governance proposes multiple authorities coordinating rules—but history shows these structures often devolve into fragmentation or central power: think of how international financial standards tend to consolidate power, or how EU directives centralize policymaking over time.

Red lines and bans (e.g., “no autonomous weaponization”) are essential, but if they’re defined too broadly or locked in without clarity, they freeze out experimentation and innovation. The result can be over-sanitized systems that lack nuance or context.

Soft guardrails—privacy thresholds, misuse detection, resource limits—offer flexibility, but only if we’ve already anticipated the relevant threats. They inherently rely on the known; unknown risks slip through the cracks.

The worry is drift: a safety system that seems adequate locally but slowly erodes trust as it scales. And when trust erodes, people disengage.

In the tech world, customer churn is a key signal. When users stop using a product, it’s rarely random — it tells you something is off. Maybe the UI went clunky, the value isn’t clear, or trust is eroding, because the overarching vision is flawed.

Exit in the context of AGI is the same, but more urgent. When people opt out—going off the grid, rejecting smart infrastructure, choosing analog in a digital world—it’s not fringe behavior. It’s a signal: the system has failed to serve, adapt, or respect human needs at the edges. Without mechanisms to hear and respond to those signals, we risk creeping toward brittleness, or worse, a collapse.

Approaches We Explored

Here are several possible approaches to AGI safety — each with promise, but each carrying their own traps.

1. Continuous Governance via Equations

Formal optimization frameworks, like the Scale-Relative Governance Equation (SRGE), attempt to encode invariants, guardrails, and spillover budgets into a single system. This makes externalities quantifiable, a major step forward compared to vague principles.

Pro: Provides a rigorous, measurable framework. Similar approaches in economics (Pareto efficiency) and control theory have proven useful in managing complex trade-offs.

Con: These models inevitably rely on complete inventories of hazards and constraints. As history shows — from nuclear safety to financial regulation — it’s impossible to anticipate all future risks. Unknown unknowns break the system.

2. Federation and Polycentric Sovereignty

A polycentric model distributes decision-making across multiple jurisdictions or actors, avoiding single points of failure. Elinor Ostrom’s Nobel-winning work on polycentric governance of commons often gets cited as inspiration.

Pro: Prevents immediate capture or monopolization of safety decisions.

Con: Federations drift. They either fragment (e.g., the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Brexit from the EU) or centralize (e.g., EU Commission power consolidations). Either way, they tend toward fragility over time.

3. Divergence-forcing Mechanisms

This idea borrows from biology: force variation into the system, ensuring no single monoculture dominates. It’s analogous to how biodiversity protects ecosystems from collapse.

Pro: Encourages resilience through variation. If one cluster fails, others persist.

Con: If pushed too far, divergence produces combative non-normality — groups become so different they generate friction, misunderstanding, or even conflict. Historical analogues exist in forced cultural separations, which often exacerbate tensions rather than stabilize them.

4. Exit as Safety Valve

Allowing individuals or groups to “exit” when systems fail them creates a form of accountability. In theory, this mirrors Albert Hirschman’s classic Exit, Voice, and Loyalty framework: exit is a corrective pressure when voice is ignored.

Pro: Preserves sovereignty; keeps systems honest by giving people a way to walk away, without losing their rights, assets, lifestyle, or status in society.

Con: Without safeguards, exit devolves into coercion or dystopian exclusion. When leaving means losing property, community, or rights, exit becomes punishment rather than signal.

The Pros and Cons in Context

Each approach to AGI safety that we explored carries real promise, but also hides within it the seeds of failure. Mathematical frameworks, for example, bring rigor and measurability. Yet these models are only as strong as the assumptions behind them. The history of financial risk modeling (equations such as Value at Risk) looked airtight until the 2008 financial crisis broke everything… which shows how even the most sophisticated formulas don’t see it all.

Federation and polycentric governance offer another path. They are designed to prevent any single actor from capturing all authority. Distributing decision-making across jurisdictions seems, at first, to preserve resilience. But history suggests otherwise. Federations tend to oscillate between two poles: fragmentation or centralization. Ancient Greek leagues splintered into rivalry, while modern supranational unions like the EU reveal the gravitational pull of central power. What begins as distributed governance often evolves into either chaos or uniformity, neither of which is stable.

The idea of divergence-forcing mechanisms borrows directly from ecology. In nature, biodiversity protects systems from collapse: when one species or crop fails, due to natural causes or direct harm by a competing species, others persist. Applying this to AGI governance suggests we should encourage natural variation across systems, so that no single monoculture dominates. But divergence, if pushed too far, creates combative non-normality. Groups become so different that they no longer cooperate or even recognize one another’s legitimacy. Historical attempts to enforce cultural separations or extreme decentralization show how quickly resilience can turn into friction and eventual conflict.

Exit, finally, seems the most human of all mechanisms. It allows people or communities to walk away when systems fail them. In political and economic theory, Albert Hirschman’s Exit, Voice, and Loyalty described exit as one of the most powerful corrective signals: when voice is ignored, exit forces institutions to notice. But here, too, lies danger. If exit comes at the cost of losing property, rights, or community, it ceases to be corrective and becomes coercive. Instead of keeping systems accountable, it creates fear. Exit becomes exile.

Each of these paths, then, is incomplete. Equations risk overfitting, federation drifts toward brittleness, divergence can fuel division, and exit can devolve into punishment. The paradox is that every solution contains within it the seeds of its opposite problem. Rather than searching for one silver bullet, the task is to weave together the strengths of these approaches while neutralizing their weaknesses.

Toward a Solution: 10 Ethical Invariants + Exit as Canary

If every proposed mechanism contains the seed of its opposite problem, then the way forward is not to pick one but to combine their strengths into a more resilient framework. What this requires is both a moral floor that cannot be crossed and a sensitivity to early signals that something is going wrong. In other words, a set of universal ethical invariants paired with exit as an early-warning system.

The first pillar is the 10 Red Lines.

No Theft (Stealing is Unethical) → Protection of property & data integrity.

No False Witness (misrepresentation of others) → Truth in attribution & lineage.

No False Testimony (lying in governance) → Auditability & honest evidence.

No Murder → Absolute ban on targeted lethal harm.

No Family Abandonment → Systems must not undermine human caregiving obligations.

No Personal Harm → Safety for individual dignity and health.

No Genocide → No systemic targeting of groups.

No Forced Belief → No coercive ideological enforcement.

No Exploitation of Rest → Protect cycles of human rest (anti-burnout, anti-slavery).

No Existential Threats → No actions that endanger humanity as a whole.

These are not technical constraints, subject to revision with every new research paper or hardware advance. They are ethical boundaries, wide enough to capture what humanity has consistently rejected across cultures and eras. Theft, false testimony, murder, genocide, forced belief, abandonment of family, exploitation, threats to rest, and existential risks to the species — these are not controversial rules of thumb, they are the bedrock of human moral order. Framing them as constitutional invariants ensures that the governance of AGI is not endlessly reactive but anchored in principles no engineer or policymaker can casually override. Where technical invariants like “no unbounded self-replication” or “emergency stop at every layer” enforce safety at the machine level, these ethical invariants preserve dignity and meaning at the human level.

The second pillar is exit reframed as canary.

Every exit is a diagnostic, not a tolerated loss.

If many exit, trust has collapsed.

If few exit, blind spots remain — equally serious.

Monitoring exits provides leading indicators of systemic risks long before collapse.

Too often, exit is treated as abandonment or even betrayal: those who leave are written off as fringe actors, unwilling to adapt. But in truth, exits are among the most important signals a system can receive. Just as customer attrition in business tells us that a product has lost trust or utility, so too does human disengagement from social, technological, or political systems. The off-grid nomad, the analog radio user, the community that resists digital encroachment… are not anomalies to be ignored. They are canaries in the coal mine. Their departure signals that something deeper is misaligned, that the system is eroding.

The Mathematics of Harmony

This is where a mathematical frame can help us move from intuition to accountability.

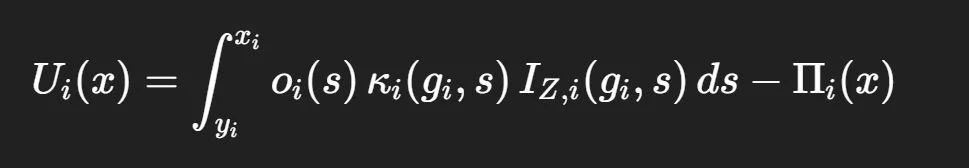

At each scale, the system’s utility can be modeled as an engine of accumulated governance impact:

Here, each cluster or actor integrates its own objectives “oi”, coupling factors “κi”, and invariant checks “IZ,i” across the span of its operation. The penalties “Πi(x)” capture privacy leakage, compute bursts, friction, or loss of trust. This is your “engine,” measuring lived utility of governance at each scale.

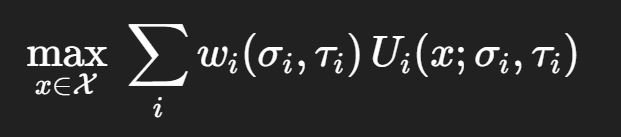

But no engine runs in isolation. To coordinate them, we require a traffic system that balances across scales, prevents externalities from cascading, and enforces the 10 Red Lines. That broader optimization takes the form of the Scale-Relative Governance Equation (SRGE):

Subject to:

Im(x)=0 for all red-line invariants (ethical and technical),

Ck(x;σk,τk)≤0 for negotiable guardrails,

Ei→j(x;σi,σj)≤ϵij to bound cross-scale spillovers.

This union of the engine and the traffic system gives us something powerful: a way to respect human ethics at the core, witness impact at each scale, and coordinate outcomes without collapsing into centralization or chaos. And because exit is not noise, but signal, the model explicitly penalizes designs that drive people away: this is the incentive to continuously improve (just like any software adoption model… user-churn = bad).

Where ExitSignal(t) amplifies the voice of the canaries — early warnings that something is broken.

Together, these two elements — the ethical invariants that ground us and the exit signals that guide us — are reinforced by a formal model that ensures accountability. The math is not the solution by itself, but it makes drift, attrition, and ethical breaches visible and measurable. That visibility is what keeps the system humble, honest, and responsive at the edges.

The Edge Principle: Harmony Is Found at the Margins

Resilient systems do not find harmony by enforcing rigid uniformity from the center. Nor do they thrive by pretending perfection can be achieved once and for all. Instead, harmony emerges at the margins, where problems and frameworks converge, where systems are forced to adapt, and where the smallest gestures can restore balance.

This is the paradox of safety: the great challenges are rarely solved by sweeping declarations or universal rules. They are resolved at the edges, where human beings experience friction, vulnerability, and risk. In those moments, what restores integrity is often not another constraint or another law, but something more subtle — a kind gesture, a moment of grace, the preservation of rest, or the courage to listen to dissent. These seemingly small corrections at the edges ripple outward, preventing fractures from spreading across the whole.

AGI governance, if it is to endure, must learn this lesson from nature and from history. Systems that fail at the margins collapse, even if they appear stable at the core. A company can boast of global success while losing its most creative employees. A government can declare order while ignoring the voices of the disaffected. A technology can scale to billions while quietly bleeding trust among its earliest adopters. In every case, the collapse begins at the edges, and the warning signs were there if only someone had listened.

This is why the principle of edge-sensitivity matters so deeply. It demands that we treat anomalies, minority concerns, and exits not as background noise but as the most valuable signals we have. It reframes perfection not as flawlessness, but as a relentless commitment to humility and refinement — to paying attention where the system rubs raw against reality.

If AGI is to serve humanity, it cannot be “almost right.” Almost-right is wrong. It must operate at near-perfection in its respect for human dignity. That standard is not achieved through grand architecture alone, but through continuous attention at the edges — where harmony is either broken or restored.

Conclusion

AGI governance cannot be only math, nor only law. It must be both — grounded in ethical invariants and sensitive to edge signals.

The brutal truth is: almost-right is wrong. If AGI is to serve humanity, it must operate at near-perfection in respecting human dignity. That doesn’t mean freezing innovation; it means listening harder at the edges — to the canaries, the dissenters, the off-grid experimenters — and refining continuously.

“Isn’t exit just fragmentation?” → “No—treated as early warning + rights-preserving, it’s diagnostic.”

“Who sets the 10 invariants?” → “They’re ethical floor; technical invariants operationalize them.”

“How do we prevent centralization?” → “Divergence without coercion; exit rights; canary weighting.”

Because if the system cannot hear its exits, it cannot survive its future.