Designing for Wisdom: AGI Governance

Introduction

Governance is, at its heart, a problem of scale. Rules and principles that make sense for one domain collapse when naively extended to another. The ethics of a family are not the ethics of a city. The economics of a firm are not the economics of a nation. The diplomacy of a nation is not the diplomacy of the globe.

We're used to thinking about problems in terms of size, like small-scale (your neighborhood) or large-scale (the entire world). But what if the "right" solution depends on which scale you're looking at it from? What if a policy that helps a big company by cutting costs ends up hurting the local community's social fabric? It's not that one is right and one is wrong; they're just looking at the problem from different vantage points.

This conflict, caused by opposing scales, is the core issue.

The challenge becomes more pressing as artificial intelligence enters the fold. AI systems — particularly those approaching AGI-level capacities — increasingly make or mediate governance decisions across multiple scales simultaneously. What is lacking is a formalism that makes explicit why conflict between scales is inevitable, and why ethical reasoning cannot be collapsed into a single, universal axis of truth.

To address this, I’ve developed a formal equation designed not to replace moral judgment but to quantify perspective. The model treats governance as an optimization problem over a continuous axis of scale, thereby rendering ethical conflict visible in structured, mathematical terms. My idea, called Natural Governance, gives us a way to solve this. It's a mathematical framework that helps us figure out if a policy fits its environment

The Natural Governance Framework

Instead of arguing about who's right, we can use a formula to see a policy at respective scale.

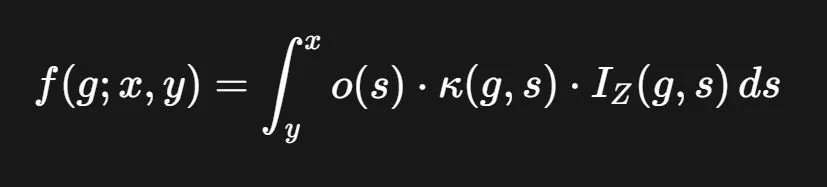

Here's the core of the idea:

Let's break that down:

Scales (s): This is the core variable. It represents any size or scope, from a single person to a whole planet. We're looking at a range of scales, from a small one (y) to a large one (x).

The Policy (g): This is the idea we're testing. It could be anything from a new law to a business strategy.

Sustainability Density (o(s)): This is how much is at stake at a given scale. For a local issue, this might be the health of a local river; for a global issue, it could be climate stability. The more that's at stake, the more important a policy's performance is at that scale.

Harmony (κ(g,s)): This measures how well the policy "fits" at a given scale. For example, a policy that encourages local farms would have a very high harmony score at a local scale but a low one at a global scale.

Constraints (IZ(g,s)): This is a simple "yes" or "no" for whether the policy is even possible at that scale. It could be due to a law, a technological limitation, or a fundamental moral principle. If it's not possible, the whole calculation for that scale becomes zero.

The formula takes all these factors and integrates them to produce a single number, f, which represents the policy's overall "function" or fit, across scales.

The Intent of the Equation

This framework helps by providing a common language and a way to make our assumptions clear.

From the Company's Perspective (Large Scale)

Scale (sC): The company operates at a large scale, which could be regional, national, or global.

Governance Concept (gC): The company's policy is to proceed with a business decision, for example, a new project or a new technology, to maximize profit and shareholder value.

Sustainability Density (o(sC)): From the company's perspective, what's at stake is significant. They might define this as economic sustainability, market share, or providing products/services to a large customer base. This value is high and positive.

Harmony (κ(gC,sC)): The policy of moving forward is highly harmonious with their mission. It aligns with their business plan and strategic goals, so the value is close to 1.

Constraints (IZ(gC,sC)): Assuming the company's action is legally permissible, the feasibility function is 1.

The resulting functional value, f(gC;sC), would be a large positive number, indicating the policy is a good and ethical fit from the company's point of view.

From the Person's Perspective (Small Scale)

Scale (sP): The person operates at the smallest possible scale, a single individual.

Governance Concept (gP): The person's policy is to resist the company's action to protect their health, community, or personal values.

Sustainability Density (o(sP)): From this scale, what's at stake is equally significant. The person defines this as personal well-being, community identity, or environmental integrity. This value is also high.

Harmony (κ(gP,sP)): The company's policy is viewed as having a very low harmony score. It's seen as a direct threat to the person's values and livelihood, so the value is close to 0 or even negative in a modified framework.

Constraints (IZ(gP,sP)): The person's resistance is physically and legally possible, so this is 1.

The resulting functional value for the person's view of the company's policy, f(gC;sP), would be a low or negative number.

The Outcome: A Moral Conflict

The framework doesn't judge. Instead, it provides a clear, quantitative map of the ethical conflict. It shows that both the person and the company are acting in ways that they believe are morally correct, and indeed, they might both be morally correct, based on their respective scales of operation. The core conflict is not that one side is evil, but that the fundamental values and priorities are in opposition because of the difference in scale.

Static and Dynamic Morality

Human morality is not uniform. Some principles are permanent and non-negotiable (e.g., prohibitions on genocide, encoded in IZ, while others are contingent and evolving (e.g., attitudes toward privacy or nuclear deterrence, encoded in κ(g,s). The equation respects both: constraints capture the static floor of morality, while harmony functions express the dynamic ceiling.

The Scale-Contingency of Ethics

It is tempting to describe this framework as moral relativism, but that would be incorrect. Relativism implies that all perspectives are equally valid. What this model demonstrates instead is scale-contingency: the evaluation of a governance action changes with the observer’s frame, but truth itself is not abolished. Conflicts arise precisely because multiple perspectives can each justify themselves internally, yet they cannot all be simultaneously true across scales.

Quantification Without Automation

A core concern is that mathematical formalism could tempt policymakers or AI systems to abdicate ethical wrestling entirely. The model is explicitly designed to resist this. It does not produce “the answer” but reveals why competing answers exist. It is a framework for accountability.

Real-World Applications

Example 1: The Local Factory

Corporate Scale: Jobs, growth, and efficiency dominate. o(s) is high, κ(g,s) is strong, feasibility is clear. Result: positive evaluation.

Community Scale: Health, identity, and environment dominate. o(s) is also high, but κ(g,s) is low. Feasibility contested. Result: low/negative.

Insight: Conflict is not about “right vs. wrong” but about incompatible scale-contingent perspectives. The framework makes this explicit.

Example 2: Nuclear Deterrence

National Scale: Retaining nuclear weapons maximizes survival against existential threats. High o(s), high κ(g,s).

Global Scale: The same policy erodes global security. High o(s), low κ(g,s).

Insight: Both evaluations are internally rational. The conflict arises because morality at one scale produces a conclusion opposite to morality at another.

Example 3: The Individual Dissenter

Individual Scale: An activist fighting for human rights maximizes harmony with long-term humanity. o(s) is high, κ(g,s) near 1.

Nation-State Scale: The activist destabilizes the status quo. From this perspective, κ(g,s) is near 0, feasibility constrained.

Insight: Both sides can justify themselves internally, but they cannot both be true. Judgment must come from dialogue and discernment across scales.

Toward a Theory of Scale-Contingent Morality

What emerges is not relativism, but scale-contingent morality:

Morality is not arbitrary or “relative”; it is contingent on the specters within their respective scale.

The governing law (the equation) remains invariant, but different scales yield different evaluations based on who’s observing them at their scale.

Conflict arises because internally consistent but mutually incompatible perspectives coexist because their operating at different scales.

This does not eliminate moral wrestling. It clarifies the terrain on which it takes place.

Closing Reflections

The temptation in AI ethics will be to use formalisms like this to automate decisions. That would be a mistake. Wrestling with ethics is not a flaw of human history; it is the very mechanism by which we grow wiser. The true power of this framework allows us to see where our scales diverge, why our moral evaluations conflict, and how perspective itself is the hidden variable in governance.

In an age where human and artificial intelligences will increasingly govern together, we need not less wrestling, but more informed wrestling.